Translation of the Opening Speech of the Alcalá de los Gazules Feria1, 28 August 2009, by Bibiana Aído, Minister of Equality

Spanish original

Dear Mayor, Consejero, President of the Deputation, Senior Romera

2, Honorary Romeras, Authorities and Friends,

I could have begun tonight by acknowledging how honoured I am to have been invited to give this opening address; I could have begun by dedicating eulogies to our town, or talking about the history of our feria over more than century and a half; I could have begun with the famous phrase of Lorca's

3, or with some borrowed verse. But of all the possibilities that occurred to me, I want to begin tonight by giving thanks to those of you who are listening to me, the people of Alcalá.

Thank you for being noble, genuine, straightforward, tenacious people … good people. Thank you for always having been so. Because although I have never left Alcalá, I have daily proof that Alcalá has never left me either. I notice it every day, whether I am close by or far away, for wherever my steps lead me in life, I run into my fellow countrymen and women.

I always have someone from Alcalá nearby. And when life brings me pain or melancholy, my memory always returns here, to Alcalá, to unite me with the memory of my own people.

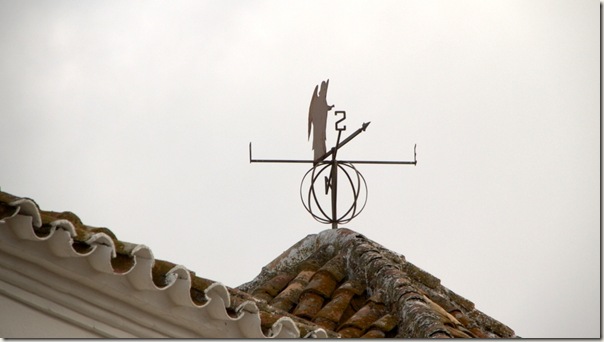

To unite me with the memory of my people, that history which stretches from the Laja de los Hierros, with its prehistoric rock carvings from the era of the Turdetanos, or the first Roman inscription in Spain, which was found on the Mesa del Esparragal and which today is conserved in the Louvre museum. In the jigsaw puzzle of my memories, they are pieced together with the long-disappeared Visigoth churches, or the two sentinels which stand watch over our town; the castle and the Parroquia

3.

To open any festival or a fair is a great responsibility; you are made welcome and invited to enjoy a few days of greetings and shared embraces, but this is more than that, it is about opening the feria which formed part of your childhood longings and concerns; you are obliged to carry out an exercise of confronting your memories and returning to the past; you are obliged to sit down and contemplate part of your own life, and also to acknowledge the selective gaps in your memory.

With this backward look, the first feelings of nostalgia start to flower, distant voices make themselves present, places you no longer visit start to become familiar again.

I was back once more in the courtyard of the Beaterio

4 during the break, and found myself once again trying to avoid the attentive eyes of the Sisters and teachers in order to to go off and play. I was back on a Saturday afternoon in this park, which once again had walls, and we ran round and hid from Angelito when he turned off the lights and it was time for the curfew. I was back eating bread from the Puerto la Pará, and once again I rode on horseback in Las Porquerizas, I spent a rainy afternoon drinking stewed coffee in the Venta de Patriste, and I was back doing sums again, and I didn't have enough fingers to count the loved ones I still have in my town.

I was able, as well, to wander through past ferias which filled me with excitement every September like the sun setting on a summer which refuses to end. And I saw myself in my new costume, in the house of my grandmother Pepa, who gave me 20 duros to buy odds and ends; I saw myself waiting in line to buy candyfloss, while thinking that there had to be something magic about that pink cloud which you could eat; I saw myself frightened to death on the ghost-train, and I saw myself holding my parents' hands to go up on that big wheel which appeared to me so enormous and majestic.

I was very small, and I remember that I wanted to grow up so I could go up in those swinging cradles on my own, to fly up high, to go round and round without stopping, to discover what it felt like to be alone so high up, and to stay in that same place for ever.

To come home, year after year, to meet up with people who are pleased to see us and whom we are pleased to see, to go back to our beginnings, to know that we are not alone; that is what the feria still means to me and to the majority of those who had to go away in search of a better future.

There were many such people, and there continue to be too many. People from Alcalá have gone away to all parts of the world. We are everywhere. But in each man or woman from Alcalá who goes away, we have an ambassador for our town, extending our geographical limits, our living space; because nobody can take away our love for our roots, for our people, and we extend these sentiments to many other people who are also starting to feel like part of our community.

And Alcalá goes on welcoming its newly-adopted children, like Matthew Coman, member of one of the best musical groups in the UK and one of the founders of the International Music Festival 'Al-Kalat', today consolidated as once of the Province's unmissable cultural dates in the summer. Or, in the past, like Maria Francisca Ulloa la Partera, the midwife who came from Utrera to help give birth to three generations of Alcalainos, and after whom one of our streets is named.

I have been able also to return to my adolescence, when a yellow card on the bumper cars was a treasure which gave us enormous but short-lived power. I revisited the Alambique, the Luca, the Paco Nono disco, the municipal marquee, the bullfighting club, and that of the Friends of the Camino, when those exciting September days arrived. I went back to my first auction to be allocated a room at [the Sanctuary of] Los Santos, which we called the “wardrobe” because of its diminutive size, and another one some years later, in which we managed to get the “dining room”, the biggest and most desirable room of all. I went back to dancing sevillanas and taking part in the procession, partly on the cart, partly on horseback and partly walking, and getting some soup at the stopping-point on the way to build up the strength to reach Los Santos.

To reach Los Santos, and to see it - because as the words of that popular sevillana go, “We are all happy under your cloak”. And that's the great thing about it, that everybody loves it. As I once heard from our world-famous Alejandro Sanz

5, there may be atheists in Alcalá, but they can't touch the Virgin of the Saints. There may be people who don't believe in gods or in religions, but who still believe in the Virgin of the Saints, in that old lady who is waiting in a corner for anyone who leaves her an offering, a prayer or a complicit wink.

I remember how proud I felt when, as the provincial delegate for Culture, I was able to contribute to the restoration of the paintings in the dome of the Sanctuary. Deep down, here amongst us, I felt as happy as if I was contributing to the restoration of the house of an old friend.

How many people have you seen born! How much talent under these skies! I could speak of philosophers like Antonio Millán Puelles or Fernando Casas; of writers like Juan Leiva, who from Jerez continues to ecupulavoke memories of Manuel Marchante´s old school and his escapades on the Alcalá hilltops.

I could speak of flamenco artists like Joaquin Herrera, and recallthat even El Camarón had flamenco roots in Alcalá according to a native of these parts, or Juan Romero, who is married to the poet Lola Peche from Algeciras, who has given us one of the most beautiful descriptions of our town:

Alcalá de los Gazules … the unordered white cluster of your houses, hanging amongst the gay greenery, blown by the wind like a victory flag, bordered with evergreen laurels. Give me a welcome, under your resounding blue sky, that I will remember you by with joy, forever, forever ...”

I could speak of politicians too, many of them but one amongst all others: Alfonso Perales

6, whose name I still can't conjugate in the past tense.

I could speak of Sainz de Andino, who founded the Madrid Stock Exchange but whose liberal ideas led him into exile in France on two occasions. He opposed the return of the absolutism of Fernando VII, like many of us who continue to oppose absolutism of any kind, above all that of people who believe they are always in the right.

I could speak of Juan Lobón and his world

7, which is a world of adventure, of the emotion of the woods, that forest of cork-oaks which surrounds us and reminds us that the human being is not the king of creation but a just a fragile part of it, and full of questions about this marvellous spectacle we call nature.

I could speak of other legendary characters of ours, like Batata or Potoco. I could speak of the cork-gatherers, the farmers, and in general, the efforts of workers to bring forward our land.

But above all, tonight I would like to bring to mind and express my recognition and gratitude to all the women of Alcalá. To those remembered and those anonymous, to those of yesterday and those of today. To those who carried out their household tasks day after day. To the young women who struggled, studied and worked to have a better future. To the grandmothers, to all those women who gave up their leisure time to dedicate themselves once more to caring for children, this time their grandchildren. To them, because they are supporting us in these years of change between the reality we have now and that which we aspire to construct.

To their daughters, mothers in their turn, who don't want to give up their dreams, their professional careers, their own lives. Women who have to balance their time, coping with being away from the home, doing two or even three jobs each day … And to all the others, those who have gone away, those who have returned, those who have come here for the first time. Those who crave knowledge and who go to the Adult Learning Centre to study what they couldn't before. Those who make ends meet, those who can't make it to the end of the month, the widows, those who live alone, those who don't get discouraged, those who help others, those who suffer in silence, those who decide to speak out, those who resist, those who dream … To those many women that make this town, each day, a better place to live in.

One of the best places to live in, to share. A place of “sailors of the land”, of mermaids stranded on the banks of La Janda, and perhaps that is why, maybe because we pine for the cool air of the seaports, we have so many marine names

8 in our midst, which go on causing confusion to some of our visitors.

And it's true that names don't matter much here, as we well know from the Calle Real, which has had so many other names but which goes on proudly calling itself Calle Real. Like the Plaza de la Cruz, which is known as the Alameda.

A capricious construction of playing-cards, fragile and whiter-than-white, on a hill which rises up from the emerald green of the countryside. This is how Alcalá is described by Manuel Peréz Regordán from Arcos de la Frontera.

For me, that deck of cards takes shape as if forming part of the story of Alice in Wonderland. And in any case it is a hand full of hearts, including gazpacho, la Coracha, el Picacho, and the fervour for our patron lady.

But above all, it is somewhere we can take real pride in feeling ourselves brothers and sisters of this landscape, witnesses to the centuries, accomplices of the Gazuls, that keeps us trying to prevent our town getting gored by life's horns. According to our contrary names, Alcalá has a beach, it has a port and it has salt mines. But above all, it has a supportive and charitable heart which beats more strongly than ever when the feria arrives.

A few years ago, I had the honour of giving the opening address at the celebrations of St George and I asked our patron saint to convert himself into a messenger of peace. I requested that friendship and conviviality should be the queens of the Fiesta, with tolerance and respect as our dancing partners. I implored him to slay the dragon of ignorance, evil and injustice, and to go on fighting every day for a future full of hope and love.

Today I address our patroness, our Virgin of the Saints, patroness both of those who believe and those who don't. And I ask her to banish evil and meanness. That she should not forget us in the business of living our lives, nor in the worthy business of working each day with energy and confidence in a better tomorrow. To liberate us from attacks of fanaticism, and also from resentment, tension and confrontation: “That which unites us is always greater than that which separates us”. Let us build a culture of peace, where there is no room for contempt toward the dignity of others. Let prosperity and well-being reign in our town.

And let time stand still during these days of Feria, let the hours not pass. Let us all be together and let nobody be left out.

They say that the future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams. Today I went back to seeing things the way I did when I was a little girl, how I longed to be able go up alone in the big wheel to see what it felt like, and I can assure you all, that nothing would have given me more pleasure, then, than to see myself standing here right now, shouting out:

LONG LIVE THE FERIA!

LONG LIVE ALCALÁ!

Translated by Claire Lloyd

Footnotes

1. A Spanish “feria” is a cross between a fair and a festival, lasting for several days and involving music, dancing, fairground rides, eating, drinking and dressing up in traditional flamenco costume.

2. A participant in a religious procession, in this case the “Romeria” from Alcalá to the Sanctuario de los Santos which takes place early in September.

3. The Parroquia de San Jorge, or Church of St George, at the top of the town.

4. Colegio Beaterio Jesus María y José – a Catholic infant school in Alcalá.

5. A famous pop singer whose family comes from Alcalá.

6. A leading socialist politician and former government minister who died in 2006.

7. A fictitious local poacher in a novel by Luis Berenguer, El Mundo de Juan Lobón.

8. For example the oddly-named Paseo de la Playa.